RWA Tokenisation Future Blueprint: Comprehensive Analysis of Underlying Logic and Pathways to Large-Scale Application Implementation

In 2023, the most eye-catching topic in the blockchain field is undoubtedly the tokenization of real-world assets (RWA). This concept has not only sparked heated discussions in the Web3 world but has also attracted significant attention from traditional financial institutions and regulatory bodies across various countries, being viewed as a strategic direction for development. Authoritative financial institutions such as Citibank, JPMorgan Chase, and Boston Consulting Group have successively released their research reports on tokenization and are actively pushing forward related pilot projects.

Furthermore, the Hong Kong Monetary Authority explicitly stated in its annual report for 2023 that tokenization would play a key role in Hong Kong’s financial future. Additionally, the Monetary Authority of Singapore, in collaboration with Japan’s Financial Services Agency, JPMorgan Chase, DBS Bank, and other financial giants, launched an initiative named “Project Guardian” to deeply explore the immense potential of asset tokenization.

Despite the high interest in RWAs, observations indicate that there is a divergence in understanding and considerable debate about its feasibility and prospects within the industry. On one hand, some views suggest that RWA is merely market hype that does not withstand in-depth scrutiny; on the other hand, there are individuals who are confident in RWA and optimistic about its future. Meanwhile, articles analyzing various perspectives on RWA have emerged like mushrooms after rain.

Through this article, the author hopes to share insights on RWA, offering a deeper exploration and analysis of its current state and future.

Author:

ZHEXIN WAN(X:bocaibocai @wzxznl)

Core Insights:

● The logic behind RWA in Crypto mainly revolves around how to transfer the income rights of income-generating assets (such as US Treasury bonds, fixed income, stocks, etc.) to the blockchain, pledge off-chain assets on the blockchain to obtain liquidity of on-chain assets, and move various real-world assets (such as sand, minerals, real estate, gold, etc.) onto the blockchain for trading. This reflects the one-sided demand of the crypto world for real-world assets, facing many obstacles in terms of compliance.

● The future focus of Real World Asset Tokenization (RWA) will be a new financial system using DeFi technology, driven by traditional financial institutions, regulatory bodies, and central banks, and built on permissioned chains. To realize this system requires a combination of computational systems (blockchain technology), non-computational systems (such as legal frameworks), on-chain identity systems and privacy protection technologies, on-chain legal currencies (CBDCs, tokenized deposits, legal stablecoins), and a robust infrastructure (low-barrier wallets, oracles, cross-chain technologies, etc.).

● Blockchain is the first technology that effectively supports the digitization of contracts following the development of computers and networks. Thus, blockchain is fundamentally a platform for digital contracts, with contracts being the basic form of asset expression, and tokens serving as the digital medium for assets after contract formation. Hence, blockchain becomes the ideal infrastructure for the digital expression/tokenization of assets, i.e., an ideal foundation for digital/tokenized assets.

● As a distributed system maintained by multiple stakeholders, blockchain supports the creation, verification, storage, transfer, and execution of digital contracts and other related operations, solving the problem of trust transmission. As a “computational system,” blockchain fulfills the human demand for “repeatable processes and verifiable results.” Thus, DeFi has become a “computational” innovation in the financial system, replacing the “computational” part of financial activities with automated execution, achieving cost reduction and efficiency while also enabling programmability. However, the “non-computational” parts, i.e., those based on human cognition, cannot be replaced by blockchain. Therefore, the current DeFi ecosystem does not cover credit, and credit-based uncollateralized lending has not yet been realized within the current DeFi system. The reasons include the lack of an identity system that can express “relational identities” on blockchain and the absence of a legal framework to protect the rights and interests of both parties.

● For the traditional financial system, the significance of Real World Asset Tokenization lies in creating digital representations of real-world assets (such as stocks, financial derivatives, currencies, rights, etc.) on the blockchain, extending the benefits of distributed ledger technology to a wide range of asset categories for exchange and settlement.

● Financial institutions can further enhance efficiency by adopting DeFi technology, utilizing smart contracts to replace the “computational” aspects of traditional finance, automatically executing various financial transactions according to predetermined rules and conditions, enhancing programmability. This not only reduces labor costs but also, in certain contexts, opens up new possibilities for businesses, especially offering innovative solutions to financing challenges for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMSEs), opening a door to immense potential for the financial system.

● As traditional financial sectors and governments worldwide continue to increase their attention and recognition of blockchain and tokenization technologies, and as blockchain infrastructure technology continues to improve, blockchain is moving towards integration with the traditional world architecture and addressing real pain points in real-world application scenarios, providing practical solutions rather than being confined to a “parallel world” detached from reality.

● In the future, under a landscape of multiple jurisdictions and regulatory systems of permissioned chains, cross-chain technology is particularly important for solving interoperability and liquidity fragmentation issues.Future on-chain tokenized assets will exist on both public blockchains and regulated permissioned chains operated by financial institutions. Through cross-chain protocols like CCIP, any blockchain’s tokenized assets can be interconnected to achieve interoperability, realizing interconnectivity across thousands of chains.

● Currently, many countries worldwide are actively advancing legal and regulatory frameworks related to blockchain. Meanwhile, the infrastructure of blockchain, such as wallets, cross-chain protocols, oracles, various middlewares, etc., is rapidly being perfected. Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs) are continuously being implemented, and token standards capable of expressing more complex asset types, such as ERC-3525, are constantly emerging. Coupled with the development of privacy protection technologies, especially the continuous development of zero-knowledge proof technology, and the increasing maturity of on-chain identity systems, we seem to be on the eve of large-scale application of blockchain technology.

Table of Contents

I. Background of Asset Tokenization

RWA from the Crypto Perspective

RWA from the TradFi Perspective

II. From the First Principle of Blockchain, What Problem Does Blockchain Solve?

Blockchain: The Ideal Infrastructure for Assets Tokenization

Blockchain’s Answer to the Demand for Computability

DeFi: Computational Breakthrough in Finance

III. Asset Tokenization: Transformative for the Traditional Financial System

Establishing a Trustworthy Global Payment Platform, Reducing Costs and Increasing Efficiency

Programmability and Transparency

IV. What is Needed for Mass Adoption of Asset Tokenization?

A Comprehensive Legal Framework and Permissioned Chains

Identity Systems and Privacy Protection

On-chain Legal Currency

Oracles and Cross-chain Protocols

Low-barrier Wallets

V. Future Outlook

I. Introduction to Asset Tokenization

Asset tokenization refers to the process of representing assets in the form of tokens on a programmable blockchain platform. Assets that can typically be tokenized are divided into tangible assets (such as real estate and collectibles) and intangible assets (such as financial assets and carbon credits). This technique of transferring assets recorded in traditional ledger systems to a shared, programmable ledger platform is a disruptive innovation for the traditional financial system and could even impact the entire future financial and monetary system of humanity[1].

Firstly, the author notes an observed phenomenon: “There are two distinct groups of opinions on RWA asset tokenization,” which the author refers to as Crypto’s RWA and TradFi’s RWA, with this article discussing RWA from the TradFi perspective.

RWA from the Crypto Perspective

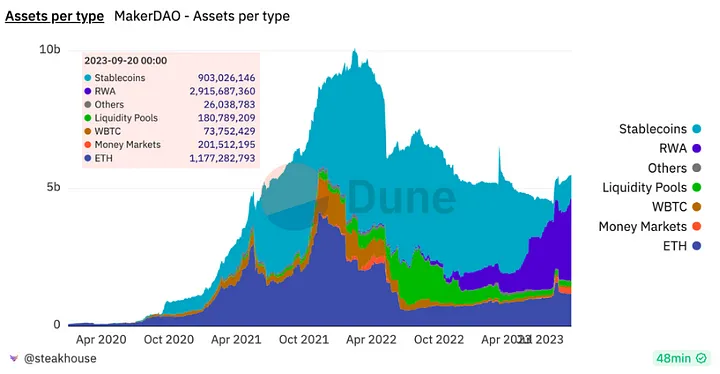

Let’s first talk about Crypto’s RWA: Crypto’s RWA, as defined by the author, represents the crypto world’s unilateral demand for the yield of real-world financial assets. The main context is the backdrop of the Federal Reserve’s continuous interest rate hikes and balance sheet reduction, which significantly impacts the valuation of risk markets and drastically withdraws liquidity from the crypto market, leading to a continuous decline in the yield of the DeFi market. At this time, the risk-free yield of U.S. Treasury bonds, around 5%, became highly sought after in the crypto market, with the most notable activity being MakerDAO’s significant purchase of U.S. Treasury bonds. As of September 20, 2023, MakerDAO has purchased over $2.9 billion in U.S. Treasury bonds and other real-world assets.

The significance of MakerDAO purchasing U.S. Treasury Bonds lies in the ability of DAI to diversify its backing assets through external credit and utilize the long-term additional income from U.S. Treasury Bonds to help stabilize its exchange rate, increase the elasticity of its issuance volume, and reduce DAI’s dependence on USDC by incorporating U.S. Treasury Bonds into its balance sheet, thus mitigating single-point risks[2]. Moreover, since the income from Treasury Bonds flows into MakerDAO’s treasury, MakerDAO has recently started sharing a portion of its Treasury Bond earnings, raising DAI’s interest rate to 8% to boost demand for DAI[3].

Clearly, the approach taken by MakerDAO is not something all projects can replicate. With the surge in MRK token prices and the market’s heightened speculation around the RWA concept, numerous RWA concept projects have emerged, beyond those larger, compliance-oriented RWA public chain projects. Various assets from the real world have been tokenized and sold on the blockchain, including some rather far-fetched assets, leading to a mixed bag of offerings in the RWA space.

From the author’s perspective, the logic behind Crypto’s RWA mainly revolves around how to transfer the income rights of income-generating assets (such as U.S. Treasury Bonds, fixed-income assets, stocks, etc.) to the blockchain, place off-chain assets on the blockchain for collateralized loans to obtain liquidity for on-chain assets, and trade various real-world assets on the blockchain (such as sand, minerals, real estate, gold, etc.).

Thus, it can be observed that Crypto’s RWA reflects a unilateral demand from the crypto world for real-world assets, which still faces many regulatory obstacles. MakerDAO’s approach is essentially the MakerDAO team using compliant methods for fund transfers (e.g., Coinbase, Circle) and purchasing U.S. Treasury Bonds through official channels to earn returns, rather than selling these returns on the blockchain. It’s important to note that the so-called RWA U.S. Treasury Bonds on the blockchain are not the bonds themselves but their income rights, and this process also involves converting the legal currency income generated by U.S. Treasury Bonds into on-chain assets, adding complexity and friction costs.

The rapid rise of the RWA concept is not solely attributable to MakerDAO. In fact, a research report titled “Money, Tokens, and Games” published by Citibank has also caused a strong reaction in the industry. This report revealed the keen interest of many traditional financial institutions in RWA, while also fueling the enthusiasm of a large number of speculators in the market. They have widely spread rumors about major financial institutions joining this field, further elevating market expectations and speculative atmosphere.

RWA from the TradFi Perspective

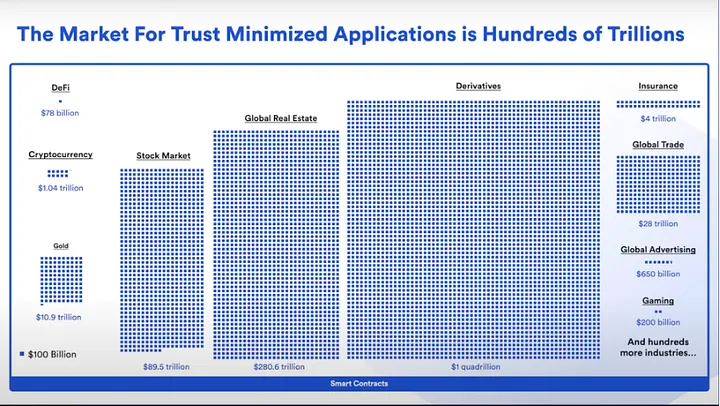

From the Crypto perspective, RWA primarily represents a one-sided demand of the crypto world for the yield of assets from the traditional financial world. If this logic is considered from the perspective of traditional finance, the scale of funds in the crypto market is minuscule compared to the trillions of dollars moved in traditional finance. Whether it’s U.S. Treasury bonds or any other financial asset, seeking an additional sales channel on the blockchain is unnecessary. The visualization below shows the scale difference between the crypto market and traditional financial markets.

Thus, from the perspective of traditional finance (TradFi), RWA represents a bidirectional effort between traditional finance and decentralized finance (DeFi). For the traditional financial world, DeFi financial services based on smart contracts are an innovative fintech tool. The focus of RWA in the traditional financial domain is on how to integrate DeFi technology to achieve asset tokenization, empowering the traditional financial system to reduce costs, improve efficiency, and address pain points in traditional finance. The emphasis is on the benefits tokenization brings to the traditional financial system, not merely finding a new channel for asset sales.

The author believes that it is necessary to differentiate the logic behind RWA because the underlying logic and implementation paths of RWA from different perspectives are vastly different. First, in choosing the type of blockchain, both have different implementation paths. Traditional finance’s RWA takes the path based on Permissioned Chain, while the crypto world’s RWA is based on Public Chains.

Since public chains have characteristics such as no entry requirements, decentralization, and anonymity, RWA projects in the crypto finance will face significant regulatory obstacles. Users lack legal rights protection in the event of adverse incidents like Rug Pulls. Moreover, rampant hacker activities demand high security awareness from users, making public chains potentially unsuitable for the tokenization and trading of a large volume of real-world assets.

On the other hand, permissioned chains used for traditional finance RWA provide basic conditions for legal compliance across different countries and regions. Establishing an on-chain identity system through KYC is a prerequisite for realizing RWA. With legal system protection, institutions owning assets can issue/trade tokenized assets in a compliant and legal manner. Unlike crypto’s RWA, assets issued on permissioned chains by institutions can be native on-chain assets instead of mapping to off-chain existing assets. The transformative potential of such native on-chain financial assets’ RWA is immense.

To summarize the core viewpoint of this article, the author believes that the future direction of Real World Asset Tokenization will be driven by traditional financial institutions, regulatory bodies, and central banks, establishing a new financial system on permissioned chains using DeFi technology. To achieve this system, a computational system (blockchain technology) + non-computational system (such as legal frameworks) + on-chain identity system (DID, VC) + on-chain legal currency (CBDC, tokenized deposits, legal stablecoins) + comprehensive infrastructure (low-barrier wallets, oracles, cross-chain technology, etc.) are required.

The following sections of this article will start from the first principles of blockchain, guiding readers through each component mentioned by the author, elaborating on its principles, and presenting actual application cases to support the author’s viewpoint.

II. From the First Principle of Blockchain, What Problem Does Blockchain Solve?

Blockchain: The Ideal Infrastructure for Assets Tokenization

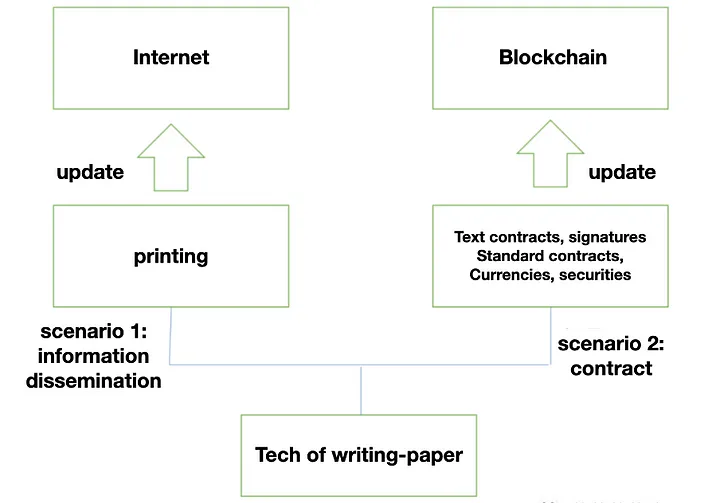

Before diving into the first principles of blockchain, it’s crucial to have a clear understanding of the essence of blockchain technology. Professor Meng Yan offers an extensive exploration of digital assets and the core of blockchain in his article “What is Digital Asset?”.[4] He posits that the invention of writing and paper is among the most significant to humanity, having an immeasurable impact on the advancement of human civilization — an impact likely exceeding that of all other technologies combined. These technologies primarily find their application in two areas: information dissemination and contracts/commands facilitation.

In the field of information dissemination, written records enable knowledge and information to be copied, edited, and spread at low cost, promoting the broad transmission of ideas and the popularization of thought. Regarding contracts and commands, writing can also document and convey various instructions. For example, ancient emperors would dispatch military orders and intelligence through written documents, bureaucratic systems would communicate orders in writing, and commercial transactions could be formalized in written contracts, recording the terms of agreements, forming consensus, and even establishing legal statutes, thereby preserving evidence for future regulation and arbitration.

There’s a clear distinction between these two application scenarios. In information dissemination, the emphasis lies on the convenience of low-cost, lossless replication, and editing. Conversely, when it comes to the transmission of contracts and directives, the attributes of authenticity, non-repudiation, and immutability are deemed far more essential. In order to meet these needs, a variety of sophisticated anti-counterfeiting printing technologies have been developed and are still widely used today. Furthermore, handwritten signatures and other verification methods continue to be employed to ensure the reliability of information.

With the advent of the Internet and the transition into the digital age, the Internet, as a modern information transmission system, greatly met the needs of information dissemination scenarios. The Internet enables the rapid, cost-efficient, lossless, and convenient transfer of information, unlocking unparalleled opportunities for global knowledge and information sharing. This era has simplified and accelerated the process of information transmission and sharing to an unprecedented degree. From academic insights to everyday data, information can now be disseminated and shared globally at an unprecedented pace, significantly advancing human societal progress and development.

While the Internet has revolutionized information dissemination, it faces challenges in managing contracts and command systems, particularly in contexts that demand authority and trust, such as corporate operations, governmental decision-making, and military command. In these critical scenarios, the reliability of information becomes paramount. Solely depending on the Internet for transmitting information could result in significant risks and losses due to inadequate credibility. This issue arises because the Internet’s development has primarily focused on its first application scenario — facilitating fast, widespread, and convenient information transfer — often at the expense of neglecting the authenticity and accuracy of the information.

In response to these challenges, the adoption of centralized decision-making and reliance on third parties emerged as primary strategies to facilitate trusted information transmission. However, centralized power structures inherently risk concentrating and misusing power, rendering the process of information transfer opaque and unjust. Moreover, entrusting third parties introduces additional security vulnerabilities and deepens trust issues, given that these entities can themselves become unreliable sources of information.

The advent of blockchain technology introduces an innovative solution to the challenges faced in managing contracts and command systems. As a decentralized, transparent, and immutable distributed ledger, blockchain ensures the authenticity and reliability of information, eliminating the need for reliance on centralized institutions or third parties to establish trust. This groundbreaking technology offers fresh perspectives and approaches to addressing information transmission issues within contract and command systems. It enables the assurance of information’s authenticity, integrity, and consistency without the necessity for centralized verification.

If the Internet represents the digital evolution of text-and-paper technology for disseminating information, then blockchain is unequivocally the digital upgrade of text-and-paper technology in the scenario of contracts and commands. Thus, blockchain can be accurately described as a distributed system, collaboratively maintained by multiple stakeholders, facilitating the creation, verification, storage, transfer, and execution of digital contracts, among other pertinent activities. Blockchain stands as the pioneering technology enabling the digitization of contracts in the era post the advent of computers and networks. Given that blockchain essentially serves as a platform for digital contracts, with contracts being the fundamental representation of assets [4], and the token acting as the digital medium for assets post-contract formation, blockchain emerges as the quintessential infrastructure for the digital expression/tokenization of assets, i.e., an ideal foundation for digital/tokenised assets.

Blockchain’s Answer to the Demand for Computability

Blockchain offers a revolutionary infrastructure capable of tokenizing assets, where smart contracts represent the foundational form of digital asset expression. The Turing completeness of Ethereum endows smart contracts with the versatility to embody various types of asset forms. This versatility has facilitated the development of token standards, including Fungible Tokens (FTs), Non-Fungible Tokens (NFTs), and Semi-Fungible Tokens (SFTs), catering to diverse asset representations.

One might wonder why only blockchain can facilitate the digital expression of assets? The answer lies in blockchain’s resolution of the “computability” challenge while simultaneously preventing manipulation. This principle, “the process is repeatable, and the results are verifiable,” is considered the foundational principle of blockchain. This is because blockchain’s operational mechanism hinges on this concept: when a node records a transaction, numerous other nodes will re-execute the recording process (ensuring the process is repeatable); if the declared outcome aligns with the results of the nodes’ independent verification, then it is accepted as an established fact within the blockchain realm and permanently documented [5].

When considering the types of problems blockchain can address, distinguishing between “computational systems” and “non-computational systems” offers a more lucid understanding of its core capabilities. Blockchain technology excels in solving problems within computational systems, where transactions are based on the principle that “processes are repeatable and results are verifiable”. Conversely, non-computational systems encompass scenarios that do not conform to the criteria of repeatability and verifiability of processes and results, such as those influenced by human cognition. This distinction raises a philosophical question: if human cognition, thought, and judgment were entirely repeatable and results verifiable, wouldn’t humanity resemble a collective of robots, all reacting identically to the same stimuli?

Throughout history, humans have inherently pursued the ability to engage in computational activities characterized by “repeatable processes and verifiable results.” Initially, due to the limitations of technological development, early humans resorted to using their physical bodies and cognitive capabilities to simulate computational processes, employing primitive methods such as counting with stones or knotting ropes for record-keeping. In ancient China, the invention of counting rods and the abacus were significant advancements that catered to the increasing computational demands of the time. However, the propensity for human error often compromised the reliability of these methods, preventing the consistent achievement of repeatable processes and verifiable results. With the advent of computers, the principle of “repeatable processes and verifiable results” has been effectively codified into computer programs, marking a significant leap in human productivity. This continual iteration and enhancement of computational tools have not only satisfied the demands for “computability”, but also served as a pivotal force propelling advancements in science, technology, and societal development.

In centralized computational systems like the Internet, the intrusion of human subjective consciousness can render the principles of repeatability and verifiability ineffective. Hackers, for example, can manipulate programs to produce varying outcomes, thereby compromising the reliability and authenticity of information transmission. This, in turn, obstructs the deliver and establishment of trust.

With the advent of blockchain technology, a novel tool emerged to fulfill the computational needs of modern society. By decentralizing the computational system, blockchain significantly reduces the potential for human subjective interference. For instance, a hacker aiming to alter the outcome of a smart contract would need to gain control over more than 50% of the blockchain’s nodes to effectuate such a change. This requirement renders the attack not only impractical but also economically inefficient, given the disproportionate cost to potential gain. Thus, except in extreme cases, blockchain technology adeptly meets the demands for computability, safeguarding the integrity and reliability of its processes and outcomes.

DeFi: Computational Breakthrough in Finance

Since the introduction of Ethereum and smart contracts, blockchain has secured a crucial role in the financial sector due to its intrinsic financial characteristics, positioning finance as one of its primary application areas. Consequently, decentralized finance (DeFi) has emerged in response to these developments, becoming the most extensively adopted application within the blockchain space.

DeFi represents a revolutionary financial paradigm that utilizes distributed ledger technology to offer a wide range of financial services, including lending, investment, and the exchange of crypto assets, all without the need for traditional centralized financial institutions. DeFi protocols achieve this through a suite of smart contracts. That means programming that encode traditional financial operations for automatic execution. Thus, DeFi transactions involve users interacting with programs capable of aggregating assets from various DeFi participants, ensuring users retain control over their funds [6].

Within the “computational system” of blockchain, DeFi — a financial system built on smart contracts — represents a pivotal computational innovation in finance. Smart contracts are poised to replace various computational processes traditionally found in finance, particularly those operations that depend on manual or mechanical efforts to achieve deterministic outcomes, such as clearing, settlement, transfers, and other repetitive tasks not contingent upon human cognition. In essence, DeFi enables the automation of traditionally labor-intensive and time-consuming financial processes through smart contracts, significantly reducing transaction costs, eliminating settlement delays, and facilitating automated execution and programmability.

The concept of a “computational system” is contrastive with that of a “non-computational system,” essentially human cognition. Blockchain operates as a purely computational system, adept at addressing computational challenges but falling short when it comes to cognitive issues. Within the financial sector, cognitive systems correlate with credit systems, including aspects such as credit evaluation and risk control systems in lending. Despite possessing identical information, such as employment income and banking transactions, different banks may arrive at varied conclusions regarding the specific credit limits to be extended.

For instance, a single customer might be granted a credit line of $10,000 by one bank and $20,000 by another. This variance is not rooted in a process that is repeatable and verifiable through calculations; rather, it is profoundly influenced by human cognition, experience, and subjective judgment. While each bank maintains its own risk control systems, human cognitive factors invariably exert a decisive influence on specific credit decisions. Decisions at this cognitive level are characterized by their non-repeatability and partial verifiability, as they blend human subjectivity and nuanced interpretations of issues that are not strictly binary.

Is it possible to address defaults in debt relationships by digitizing debt contracts on the blockchain and automating repayment processes? To delve into this question, an initial analysis of the nature of debt is essential. Debt transcends a mere contract or formality; it represents a relationship founded on the mutual recognition and trust among individuals. Fundamentally, the establishment of a debt relationship relies not solely on the contractual documentation but more significantly on human cognition and the trust it engenders.

Blockchain technology has the capability to digitize the essence of debt contracts, enabling these contracts to be programmed with specific rules that automate the repayment and debt transfer processes. This automation is both predictable and verifiable, grounded in immutable rules that guarantee the repeatability of processes and the verifiability of outcomes. However, it’s important to note that this technological framework operates without engaging the human cognitive dimension.

Although the “essence” of the debt contract has been objectively confirmed and guaranteed in technology, the formation, modification and even dissolution of the debt relationship are based on human cognition. This kind of cognition cannot be programmed or onchained. Human cognition is not a “repeatable and verifiable” process. It may change according to the environment, emotions, and information. When a debtor’s perception changes, they may choose not to pay the debt, which is the so-called “default”. Thus, blockchain technology falls short in debt default, pinpointing the issue as fundamentally cognitive rather than computational.

Some might question, can’t DeFi’s lending agreement solve the problem of borrower default through smart contract liquidation? Isn’t the act of borrowing on DeFi part of a credit system? Compound’s General Counsel, Jake Chervinsky, has articulated in an article that DeFi lending does not constitute lending in the traditional sense but rather functions as an interest rate agreement [7]. In essence, DeFi lending does not create credit in the conventional way. The operation of most DeFi lending protocols hinges on two fundamental mechanisms: overcollateralization and liquidation. For instance, pledging $100 worth of ETH to borrow $65 worth of USDT is fundamentally a form of “computational leverage” that does not produce any credit. In this model, the borrower’s commitment does not depend on any future payment, trust, or reputation promises.

To briefly summarize, blockchain, as a distributed system collaboratively maintained by multiple stakeholders, enables the digital creation, verification, storage, transfer, and execution of contracts, addressing the challenge of trust transmission. As a “computational system,” it fulfills the requirement for processes that are repeatable and results that are verifiable, positioning DeFi as a computational breakthrough in the financial sector. This innovation replaces traditional computational tasks in finance, offering cost reduction, efficiency gains, and programmability. However, blockchain’s capabilities do not extend to the “non-computational” aspects of finance, which are deeply rooted in human cognition. Consequently, the current DeFi ecosystem does not encompass credit-based uncollateralized lending, partly due to blockchain’s current inability to articulate complex “relational identities” and the absence of a legal framework ensuring the protection of parties’ rights and interests.

III. Asset Tokenization: Transformative for the Traditional Financial System

Financial services are founded on trust and empowered by information. This trust depends on financial intermediaries that maintain records of ownership, liabilities, conditions, and contracts, which are often dispersed across independently operated systems or ledgers. These institutions keep and verify financial data, enabling people to trust in the accuracy and completeness of this data.

Since each intermediary holds different pieces of the puzzle, the financial system requires a significant amount of post-hoc coordination to reconcile and settle transactions, ensuring the consistency of all relevant financial data. This is an extremely complex and time-consuming process. For example, in the context of cross-border transactions, due to the need to comply with different regulations and standards of various countries, and the involvement of multiple different financial institutions and platforms, this process is particularly complicated, making the transaction settlement cycle often longer, typically taking one to four days to settle. This process increases the cost of transactions and reduces transaction efficiency[8].

Blockchain, as a distributed ledger technology, shows great potential in addressing the common efficiency issues in the traditional financial system. It solves the problem of information fragmentation caused by multiple independent ledgers by providing a unified, shared ledger, greatly enhancing the transparency, consistency, and real-time update capability of information. The application of smart contracts further enhances this advantage, allowing transaction conditions and contracts to be encoded and automatically executed upon meeting specific conditions, significantly improving transaction efficiency and reducing settlement time and costs, especially in scenarios dealing with complex multi-party or cross-border transactions.

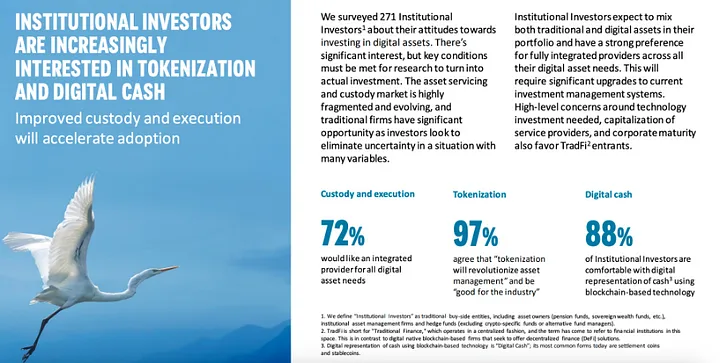

Therefore, asset tokenization is increasingly accepted by traditional finance. According to a research report from the Bank of New York Mellon, 97% of the 271 financial institutions interviewed believe that tokenization will bring about a new revolution in asset management[9], fully reflecting the potential of blockchain in the financial sector.

Therefore, for the traditional financial system, the significance of real-world asset tokenization lies in creating digital representations of real-world assets (such as stocks, financial derivatives, currencies, equities, etc.) on the blockchain, extending the benefits of distributed ledger technology to a wide range of asset categories for exchange and settlement.

Financial institutions further enhance efficiency by adopting DeFi technology, using smart contracts to replace the “computational” aspects of traditional finance. These smart contracts automatically execute various financial transactions based on predefined rules and conditions, enhancing programmability. This not only reduces labor costs but also, in certain contexts, opens new possibilities for businesses, especially offering innovative solutions for the financing challenges faced by small and medium-sized enterprises (SMSEs), thus unlocking a door to tremendous potential for the financial system.

To delve deeper into the potential transformative power of tokenization on the financial system, this article will present a more in-depth analytical framework for readers:

Establishing a Trustworthy Global Payment Platform, Reducing Costs, and Increasing Efficiency

In everyday life, financial activities, and trade activities, clearing and settlement are ubiquitous, serving as a key link in maintaining economic flow. Although these processes are extremely common in life, they are often not the focus of the public, yet they are the underlying force ensuring the smooth conduct of transactions.

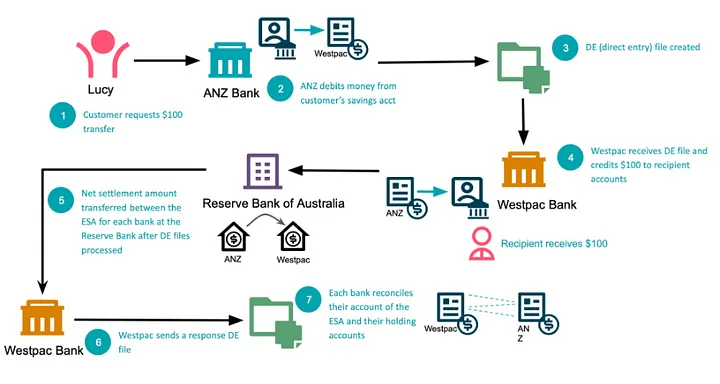

In our daily shopping, paying salaries, sharing bills, and other activities, we are involved in the process of clearing and settlement. When splitting costs with friends, we are also engaged in a simplified clearing and settlement process — calculating the amount each person should pay, making transfers, etc. Similarly, when we use Alipay or WeChat for electronic payments, the payment platform goes through a series of clearing processes to ensure that the payment is accurately transferred from our account to the merchant’s account. For users, it seems like a simple action of payment results in the transfer of money, but in reality, behind this simple action, there are many processes of clearing and settlement involved (as shown in the following figure[10]).

According to the Committee on Payment and Settlement Systems (CPSS), clearing is defined as “a set of procedures through which financial institutions submit and exchange data and/or documents relating to the transfer of funds or securities.” This all begins by establishing a “net position” for the transaction participants, which means offsetting the debts between the parties, a step known as “netting”[11].

The subsequent clearing refers to the process of exchanging, negotiating, and confirming payment instructions or securities transfer instructions, which occurs before settlement. Settlement refers to the process, including the transfer of securities or other financial instruments by the seller to the buyer and the transfer of funds by the buyer to the seller, which is the final step in a transaction. The settlement system ensures that the transfer of funds and financial instruments can proceed smoothly.

In short, clearing is where both parties send, receive, check, and confirm payment instructions and reach a final consensus on the assets to be paid, while settlement is the transfer of assets based on the results of clearing. Let’s explore this process through an example:

Clearing

Imagine you and your friends decide to split the bill after dining together at a restaurant. Everyone declares their consumption amount, and then the group calculates how much each person should pay. In this scenario:

Amount Confirmation: The amount each friend declares is akin to a payment instruction.

Communication and Verification: Everyone reports their consumption and verifies the total amount, similar to the process of sending, receiving, and confirming payment instructions during clearing.

Total Calculation: After tallying up the total bill, the amount each person is responsible for is determined, akin to exchanging payment information and confirming the final positions for settlement.

Hence, clearing is a “verification and preparation” step where parties confirm the amounts to be paid and prepare for the next step of settlement.

Settlement

In the example, once everyone knows how much they need to pay, the actual payment follows. Each person pays their share, and the collective sum equals the restaurant’s total bill. At this point:

Payment: The actual amount paid by each person is akin to the step of funds transfer.

Verification: Everyone confirms their payment is correct, verifying that each member has paid the correct amount, similar to confirming the correct transfer of funds during settlement.

Notification: If one friend is responsible for collecting all payments and paying the bill in one go, they will notify others once the payment is complete. This notification step is similar to the procedure of notifying all parties once the settlement is complete.

Thus, settlement refers to the actual movement of funds from one party to another and confirms the completion of the transaction.

It’s evident that in the traditional financial system, clearing and settlement are “computational” processes of accounting and confirmation. Parties reach consensus through continuous checking and verification, and based on this, asset transfers are made. This process requires collaboration across multiple financial departments and considerable human cost, and it may face operational and credit risks.

On June 28, 1974, a notable bank failure caught the attention of the international financial community, namely the collapse of Herstatt Bank, exposing the credit risk of cross-border payments and its potential for great destruction. On that day, several German banks made a series of foreign exchange trades from the German mark to the U.S. dollar, intending to remit dollars to New York, with Herstatt Bank as the counterparty.

However, due to the time zone differences between Germany and the United States, there was a significant delay in the clearing process. This led to the dollars being “retained” in Herstatt Bank instead of being promptly transferred to the counterparty bank’s account. In short, the expected dollar payments were not carried out as planned. During those critical hours, Herstatt Bank received a clearing order from German authorities.

Lacking the capacity to make payments, it failed to remit the corresponding dollar amounts to New York and ultimately spiraled into bankruptcy. The shockwaves from this sudden insolvency affected several German and American banks involved in the foreign exchange trades, each suffering losses to varying degrees. The incident also promoted the widespread adoption of real-time gross settlement systems in cross-border payments and the establishment of the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision[12], underscoring the importance of settlement and clearing in international financial markets.

Blockchain, with its characteristics of a distributed ledger and the immutability and traceability of data, offers a mode of transaction called atomic settlement through smart contracts. When one party pays a certain asset to another, the other party simultaneously pays the corresponding asset to the payer, eliminating the risks and costs associated with clearing and settlement while greatly enhancing the transactional benefits of real-time settlement.

By integrating blockchain technology into cross-border payment and settlement, we unveil its profound implications: it has constructed an efficient peer-to-peer payment network, mitigating the problem of prolonged clearing times in traditional cross-border payment methods. By eliminating third-party intervention, it enables all-day payments, instant receipt, and easy cash withdrawals, successfully meeting the convenience needs of cross-border e-commerce payment and settlement services. Additionally, it has established a globally integrated cross-border payment trust platform at a lower cost, reducing the financial risks brought about by cross-border payment fraud[13].

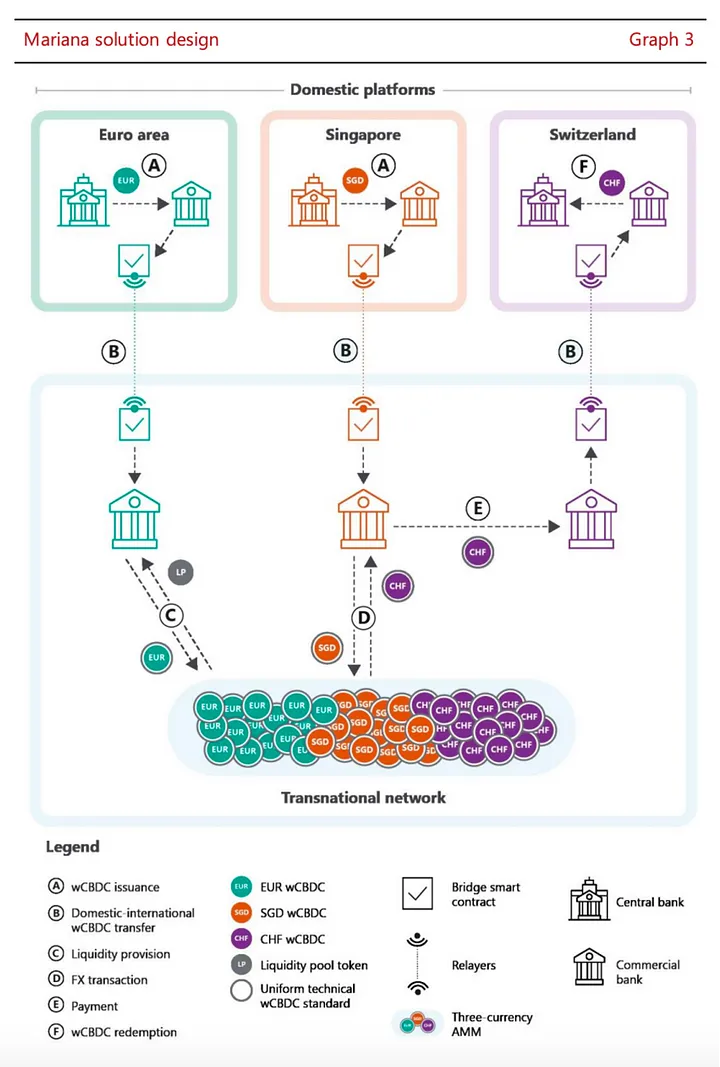

The Project Mariana, a collaborative initiative by the BIS Innovation Hub (BISIH), the Bank of France, the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS), and the Swiss National Bank, released its test report on September 28, 2023. The project successfully validated the technical feasibility of using Automated Market Makers (AMM) for tokenized Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs) in international cross-border transactions and settlements[14].

n summary, payment activities within the traditional financial system often come with cumbersome clearing and settlement processes, generating additional costs and suffering from low efficiency due to settlement delays, along with the risks of human error, credit risks, and the constraints of strict timing windows. The use of blockchain and DeFi technologies provides an effective solution.

Blockchain technology optimizes the transaction process by cutting out intermediary steps, thus significantly reducing related costs. This technology avoids the long waiting times of traditional financial settlements, achieving true 24/7 market operations, especially enhancing the speed and accuracy of cross-border payments. More importantly, with the reduction of transaction costs, the indirect profit increase might far exceed the direct cost savings, thereby promoting the vitality and efficiency of financial markets on a broader scale.

Programmability and Transparency

For the traditional financial system, the programmability and transparency brought about by the tokenization of real-world assets will introduce disruptive changes. We can use financial derivatives as an example to illustrate the disruptive effects of programmability and transparency. Financial derivatives represent an extremely large market within the traditional financial sector, with an estimated nominal value of over one hundred trillion dollars[15]. The derivatives market is vast and complex, including stocks, fixed income, foreign exchange, credit, interest rates, commodities, and different types of contracts in other markets. These types of contracts include options (regular call and put options as well as exotic options), warrants, futures, forwards, and swaps.

It is precisely the enormous potential of the leverage effect of financial derivatives that enables them to create asset sizes that are many times the value of the underlying assets. The 2008 financial crisis is a classic case of a global financial disaster triggered by financial derivatives. In this crisis, banks packaged a series of mortgage loans into a special financial product — Mortgage-Backed Securities (MBS) — and sold them to investors. For banks, this practice could transfer the original loan risks, obtain cash flow by selling these packaged mortgage loans, and earn the interest spread. For the banks, each loan issued almost became a creation of profit, generating enormous risks.

The movie “The Big Short” vividly depicts this phenomenon: when a housing loan equates to profit for banks, with no associated risk to the banks themselves, they tend to endlessly produce mortgage contracts. When creditworthy homebuyers were exhausted, banks turned to less creditworthy individuals to continue this game, where someone without any collateral could even secure a loan in their dog’s name. These low-quality “subprime loans[16]” became the catalyst for the subsequent financial tsunami.

In the backdrop of continuously rising real estate prices in the U.S. and a policy of low-interest rates and loose monetary policy, banks incessantly issued subprime loans, while Wall Street financial institutions invented various financial derivatives, such as Collateralized Debt Obligations (CDOs), which are financial instruments that bundle various MBS; and synthetic CDOs, which are packages of various CDOs and Credit Default Swaps (CDS).

Eventually, the market saw an endless emergence of complex financial derivatives to the extent that it became impossible to trace the actual underlying assets supporting these products. Coupled with a significant number of subprime loans mixed into financial derivatives rated as “low-risk,” the distortion in ratings meant that high-risk assets only required the payment of very low premiums. These layered and packaged derivatives were sold to various brokers and investors, causing the leverage of the entire financial system to skyrocket rapidly, becoming perilously unstable.

Subsequently, as the U.S. began to raise interest rates, the increase in loan interest led to a large number of borrower defaults, a problem that first became apparent in the subprime loan market. However, because subprime loans were packaged into Asset-Backed Securities (ABS), MBS, and even CDOs, the problem quickly spread throughout the entire financial market. Numerous financial derivatives, which appeared to be high-grade and low-risk, suddenly revealed substantial default risks, and investors were almost completely ignorant of the actual risks of these derivatives. Market confidence was severely shaken, and the financial market faced a massive sell-off, becoming an important trigger for the outbreak of the financial crisis in 2008. All of this stemmed from the chaos, lack of transparency, and overly complex structural system in the financial market.

Hence, the importance of transparency for complex financial derivatives is evident. We can speculate that if the technology of tokenization had been in use before 2008, investors might have been able to easily understand the underlying assets, potentially preventing such a financial crisis. Moreover, tokenizing financial derivatives could also improve the efficiency of multiple stages in the asset securitization process, such as servicing, financing, and structuring (i.e., tranching)[17].

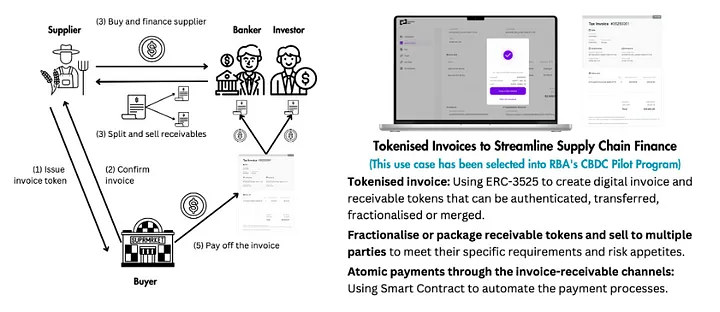

For example, during the asset securitization process, using the semi-homogeneous token standard ERC-3525 to bundle assets, the digital container feature of ERC-3525 can package non-standard assets into a divisible and combinable standard asset. Smart contracts can be used to layer these (senior, mezzanine, and junior tranches) and program the cash flows of the assets, reducing operational and third-party costs, greatly enhancing asset transparency and settlement certainty.

When using blockchain, the monitoring role of regulatory authorities can be partially undertaken by the platform. When key information, such as documents submitted by sellers, past records, and updates are visible to all key stakeholders on the blockchain platform, unilateral governance effectively becomes multilateral. In other words, any party has the right to analyze the data and detect anomalies, and this timely disclosure of information can reduce transaction costs in financial markets[17].

To further understand the benefits that programmability and transparency bring to the traditional financial system, the case of the Australian startup Unizon, selected for the Central Bank of Australia’s CBDC pilot project based on ERC-3525’s “Digital Invoice Tokenization” project, serves as an excellent example[18]. In supply chain finance, accounts receivable factoring is a common business model. It allows businesses to sell their receivables at a discounted price to a third party (usually a factoring company), thereby obtaining necessary financing to improve their cash flow.

However, due to the challenge of authenticating invoices, small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) generally lack sufficient credit backing, making it difficult for investors to conduct reasonable risk control over a large number of SMEs. This leads to widespread financing difficulties for SMEs in reality. If SMEs cannot accept delayed payments on accounts, they find it challenging to take orders from large enterprises; but accepting orders from large enterprises can strain the company’s working capital and increase the risk of cash flow disruptions.

By tokenizing invoices, we can add a confirmation step in the invoicing process using private key signatures. Once confirmed, the invoice is generated with the confirmation signatures of both parties, ensuring that the invoice is created with both parties’ acknowledgment. Considering that accounts payable delays are essentially a form of loan provided by sellers to buyers, if the authenticity of invoices can be effectively resolved, sellers could rely on the buyer’s credit to sell the receivable at a certain discount rate to a factoring institution, thus receiving discounted funds.

Thanks to the cash flow programmability enabled by ERC-3525 tokenization, in the “Digital Invoice Tokenization” scenario, payment invoices are tokenized. ERC-3525 is used to create a pair of accounts: a Payable account and a Receivable account. These two accounts form a quantum entanglement-like bound payment channel, where as soon as the buyer makes a payment to the Payable account, funds are automatically distributed to the Receivable account via a smart contract. This means that no matter how many parts the receivable is split into or who ultimately holds it, it will be transferred to the Receivable account according to the predetermined ratio. This operation, which is highly costly and difficult to achieve in the traditional financial system, can be greatly optimized using tokenization technology, significantly increasing the liquidity and composability of supply chain finance factoring, as well as reducing operational costs.

In summary, the programmability and transparency of tokenization have a profound impact on the traditional financial system. The transparency provided by blockchain platforms can reduce financial risks and problems with information asymmetry in the traditional financial system, and the programmability of tokenization opens a door that makes many operations, which are difficult to achieve in the traditional financial system, possible. It significantly reduces the need for manual intervention and third-party involvement, greatly enhancing the liquidity and composability of financial services and creating space for innovation, with the potential to breed unprecedented types of financial products.

IV. What is Needed for Mass Adoption of Asset Tokenization?

Tokenization undoubtedly brings revolutionary innovation to the traditional financial system, but to truly apply this innovation to real-world scenarios, we still face many challenges and difficulties. Here are some key factors to consider for mass adoption of asset tokenization:

A Comprehensive Legal Framework and Permissioned Chains

As a purely “computational system,” blockchain can only address people’s demands for “computational” aspects (reduced friction costs, programmability, traceability, etc.), while demands for relationship authentication, judgment, and rights protection require a cognition-based non-computational system to solve, such as a comprehensive legal regulatory framework. This is because the execution and adjudication of laws and the judgment and control of risks are based on human cognition, which is precisely what cannot be fulfilled by public blockchains. Not to mention the prevalence of hackers and security incidents in the public chain ecosystem; when a user’s wallet is stolen on a public chain, the assets are almost impossible to recover, and there is nowhere to uphold rights. The open and anonymous nature of public chains also makes regulation and law enforcement challenging.

The application scenarios of real-world asset tokenization in traditional finance involve a large number of asset issuance and trading operations. For financial institutions holding core assets, compliance and security protection are primary demands. Imagine if a financial institution issued several hundred million dollars of tokenized financial assets on a public chain, and all assets were stolen by a North Korean hacker group. In such a case, it would be impossible to recover the asset losses or to legally penalize the criminals, which is clearly unacceptable.

Therefore, the financial industry relies on a series of legal protective measures to protect investors from fraud and abuse, combat financial crime and cyber misconduct, maintain investor privacy, ensure industry participants meet certain minimum standards, and provide recourse mechanisms in case of problems. Hence, only permissioned chains can satisfy both “computational” and “non-computational” demands. We can imagine that in the future, each country or region may have different legal regulatory systems, and each area will have permissioned chains that comply with the local legal and regulatory framework to carry tokenized real assets.

Identity Systems and Privacy Protection

Relational Identity vs. Contractual Identity

If blockchain hopes to be closely integrated with the real world and achieve mass adoption, a complete on-chain identity system is key. For a long time, blockchain’s anonymity has made it difficult to reveal the true identity of wallet holders, and a system without identity verification naturally struggles to establish credit. Credit is a product of human social cognition, relying on deep social connections between people. In fact, the blockchain world has always lacked a “relational identity” system based on interpersonal relationships. This system is not a simple identity tag but a complex structure that reflects an individual’s various roles and relationships in a social network.

More than 150 years ago, the ancient British jurist Henry Maine inspired deep thinking about the nature of identity[30]. He suggested that there are two major types of identity: one is “relational identity,” which originates from an individual’s roles and interpersonal relationships in society, such as being a father, having citizenship of a certain country, or being a civil servant, soldier, etc. This identity reflects social attributes, emphasizing a person’s position in social structures and their connections with others.

The other type of identity is based on the “Contractual Status” system derived from contract execution, such as labor agreements, corporate organizational structures, and contract terms. In the blockchain domain, this can be likened to “Status” attributes formed by smart contract interactions, such as a wallet’s balance, interaction history with smart contracts, and the states generated by smart contracts.

For years, blockchain has essentially been a purely “computational system,” containing only “Contractual Status.” Specifically, on-chain information is limited to anonymous wallet addresses, their balances, transaction history, and other data. Although attempts have been made to construct a “Relational Status” system on-chain using these data elements, this contract-based identity system lacks the ability to express social interpersonal relationships and cannot fully capture or replicate the social dimensions and human interactions covered by “relational identity.”

This limitation is a significant factor impeding the development of the blockchain field, particularly decentralized finance (DeFi), such as the lack of an uncollateralized lending system based on credit. Purely contract-based identity verification cannot capture an individual’s reputation and trust because credit is built on complex human social relationships, not just the historical records of smart contracts or account balances. To realize such a credit system, what is needed is not just a technological solution but also a mechanism that can understand and reflect the complex network of human social relationships.

The current state of the identity system in the blockchain world is far from meeting the conditions necessary for large-scale applications that support the tokenization of real-world assets. In addition to the “Contractual Status” system, blockchain also needs a “Relational Status” system that can carry human social relationships and credit systems because in human society, credit is built on deep, multi-dimensional social interactions. It is not an attribute that individuals can endow themselves unilaterally, but one shaped by an individual’s behavior within a social network, their reputation, and the recognition of others. More importantly, such a credit system often requires the endorsement and certification of authoritative third parties to ensure its credibility and authority. For example, in the real world, identity proofs and related documents issued by governments or other authoritative institutions are significant indicators of an individual’s identity and credibility.

In summary, for blockchain to combine with the real world and achieve mass adoption, the identity system needs to incorporate both “Relational Status” and “Contractual Status” systems. To implement a “Relational Status” system, it is necessary to introduce authoritative third parties (such as government agencies, regulatory bodies, etc.) that can verify individual social relationships and reputations to grant, certify, and endorse identities on-chain. It also requires technological innovation to ensure the security, privacy, and immutability of identity data.

DID+VC identity system based on W3C standards

For the mass adoption of tokenization of real-world assets to be realized, the optimal solution for an identity system is needed on a technical level to achieve a dynamic balance between data sovereignty, privacy protection, regulatory compliance, and interoperability. The DID+VC system under W3C standards may be part of the answer to this unresolved issue.

To realize the tokenization of real-world assets and promote their large-scale application, a comprehensive identity solution on the technological level is urgently needed. This solution must find a dynamic balance between data sovereignty, privacy protection, regulatory compliance, and interoperability. The W3C’s Decentralized Identifiers (DID) and Verifiable Credentials (VC) framework could provide part of the solution to this complex issue.

Throughout the evolution of digital identity, we have witnessed several key stages of transformation: from centralized identity management, where identity information is completely controlled by a single authoritative entity; to federated identity authentication, which allows a certain portability of a user’s identity data and cross-platform login capabilities, such as single sign-on implemented through WeChat or Google accounts; to a decentralized identity system based on authorization and permissions, as demonstrated by OpenID; and finally, to Self-Sovereign Identity (SSI), where data ownership and control truly return to the individual, although mechanisms like zCloak Network’s zkID decentralized identity system have not yet been widely adopted.

Currently, the on-chain identity system has enhanced the anonymity and openness of identity to some extent through blockchain’s inherent cryptographic mechanisms. However, because different ecosystems and application systems often adopt closed or relatively independent data systems, users’ identity information remains fragmented and stored in isolated systems that are difficult to interoperate. Therefore, the next key challenge is to break down these silos and construct an identity verification ecosystem that can ensure personal data sovereignty and privacy while meeting regulatory requirements and having broad interoperability. This requires not only technological innovation but also deep cooperation among all stakeholders and the support of policymakers.

The World Wide Web Consortium (W3C), the organization responsible for developing international internet standards such as HTML and CSS, released the first formal standard for Decentralized Identifiers (DIDs) in 2022 and published a detailed definition and standard framework for Verifiable Credentials (VCs) in 2019.

In W3C specifications, a DID is defined as a globally unique, highly available, resolvable, and cryptographically verifiable string (for example, did:example:123). This identifier can be used to identify any form of entity, be it individuals, organizations, or objects. Each DID is generated according to a specific algorithm and is controlled independently by its owner, rather than being authorized by a single entity.

A DID can be resolved into a DID document, which contains information such as authentication keys, agreement keys, delegation keys, assertion keys, and service endpoints for interacting with the DID entity. These keys are akin to different types of documents we use for signing in various life scenarios, such as confidentiality agreements, powers of attorney, or authorization letters.

VC, the verifiable digital credential that complements DID, is essentially an endorsement-style statement from one DID to another DID about certain attributes, intended to verify the identity, capabilities, or qualifications of the DID subject. For example, a VC can be a digital certificate issued by an organization, government department, or commercial entity, cryptographically generated and verified to confirm that the owner possesses certain specific attributes and that these attributes are trustworthy. VCs can contain various information and data types, such as ID, type, timestamp, etc., and support multiple settings for the credential status, including valid, expired, revoked, suspended, etc., to reflect the issuer’s statement about the credential’s validity.

Within the VC ecosystem, the W3C standard defines three roles: issuers (attesters), holders (claimers), and verifiers. These roles participate in the circulation of a credential: the issuer verifies and issues credentials to the holder, the holder decides how and to which verifiers to present these credentials, and the verifier confirms the information they need to verify, thus completing the verification process.

https://support.huaweicloud.com/intl/en-us/devg-bcs/bcs_devg_4005.html

Building on this foundation, multiple projects and development teams have integrated privacy protection technologies that go beyond traditional cryptography into identity verification systems, including the Zero-Knowledge Proof (ZKP) technology, which is garnering significant attention in the Web3 domain. ZKP is a unique method that allows one party (the prover) to prove to another party (the verifier) that they indeed know certain information without revealing any specifics about that information.

To illustrate with a simple analogy, suppose Alice wants to prove to Bob that she knows how to solve a specific scrambled Rubik’s Cube but doesn’t want to reveal the exact steps. In this scenario, Alice could use an opaque box to solve the cube without Bob seeing the steps. She merely needs to present the solved cube from the box as proof of her skill, keeping the specific steps secret. The principle of ZKP works similarly, encrypting the true content of information within the “box” while proving a fact.

In digital identity verification scenarios, ZKP technology is particularly useful because it allows individuals to prove personal information without disclosing private details. Typically, identity verification might require revealing a lot of personal information, which, once collected and analyzed by multiple parties, could pose a threat to individual privacy. However, systems that incorporate ZKP technology, such as the zkID developed by zCloak, combined with DID and VC, offer users enhanced privacy protection options.

With the zkID system, after receiving a VC with the issuer’s digital signature, users can flexibly control the amount of information they wish to share during the verification process. Users can autonomously choose the granularity of information display, such as Zero-Knowledge Proof Disclosure, Digest Disclosure, Selective Disclosure, or Full Disclosure. Especially through Zero-Knowledge Proof Disclosure, users can present information under the “minimum knowledge principle,” merely responding with “meets criteria” or “does not meet criteria” outcomes, without revealing any specific private information.

For instance, users could prove to relevant institutions that they possess a valid visa, qualify for a loan, have the right to vote, or meet transaction standards, simply by presenting results from locally stored data validated through zero-knowledge proof. Throughout this process, users’ private data remains stored and processed on their local device, without disclosing any specifics, ensuring complete control over data usage rights rests with the user.

In summary, as we push forward with the mass adoption of tokenizing real-world assets, privacy protection and compliance in identity verification become indispensable cornerstones. By adopting DID and VC identity verification systems based on W3C standards and integrating Zero-Knowledge Proof (ZKP) technology, we can safeguard on-chain identity privacy while meeting compliance requirements. This not only provides implementation guidelines for a “comprehensive legal system” but also potentially serves as a key element in bridging the gap between on-chain and off-chain worlds, balancing privacy and regulatory needs.

On-chain Legal Currency

Blockchain applications fundamentally aim to solve trust issues, and in the commercial domain, 99% of trust-related application scenarios involve money[19]. Therefore, for the mass adoption of real-world asset tokenization, the presence of on-chain legal currency is essential. In fact, the tokenization of on-chain currency itself is an application scenario of real-world asset tokenization. Only by introducing Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs), tokenized deposits, and compliant stablecoins can the full potential of real-world asset tokenization be unleashed.

Currently, the blockchain world lacks a currency trust anchor provided by central banks[20]. Although stablecoins have emerged like mushrooms after rain, attempting to fill this void by mapping fiat currencies, the reality of stablecoins experiencing price decoupling during crypto market turmoil indicates that stablecoins cannot replace the role of fiat currency on the blockchain. Essentially, stablecoins are just “vouchers” for fiat currency on the blockchain, meaning they are not the fiat currency itself. Even in cases where the reserve assets of stablecoin issuers are fully sufficient, stablecoins can still deviate in price due to market panic. However, if the on-chain Token is the “entity” of legal currency, such price decoupling would not occur.

Compared to the current stablecoin system, using tokenized legal currency is not only more convenient and accessible, but its application scenarios are also more significant, providing greater programmable space for financial innovation. First, on-chain legal currency, combined with a consortium blockchain architecture regulated by national laws, can be directly integrated into our daily payment scenarios. It can seamlessly blend into our daily lives, whether in salary payments, commercial activities, or other aspects. This means people can directly obtain on-chain legal currency through their regular activities, bypassing some of the complex and time-consuming steps in the current crypto system, such as needing to acquire Gas fees to use wallets and stablecoins.

In the 2023 annual report by the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), known as the “central bank of central banks,” the section “Blueprint for the future monetary system: Improving the old, enabling the new” mentions that tokenization has the potential to revolutionarily impact the existing monetary system, exploring unprecedented opportunities for the current system. This vision describes a new type of financial market infrastructure — “Unified Ledger,” which integrates Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs), tokenized deposits, and other financial and physical assets’ tokenized claims.

The Unified Ledger has two key advantages. Firstly, it offers a unified platform where a broader range of emergency measures and financial transactions can be seamlessly integrated and automatically executed. This enables transactions to be settled synchronously and instantly. Contrasting with the crypto world, settlements using central bank currencies ensure the uniqueness and finality of payments. Secondly, by consolidating everything in one place, new types of contingent contracts (which become effective under certain conditions or circumstances) will emerge, better serving the public interest by addressing issues related to information and incentives[20].

To further help readers understand the importance of on-chain legal currency, I will further explain, first clarifying the definitions and differences between CBDCs, tokenized deposits, and legal stablecoins that will be widely used on-chain in the future:

Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC): Digital base money (Base Money) directly issued by the central bank. Transactions involving CBDCs directly reflect changes on the central bank’s balance sheet and can exist on blockchain platforms in a tokenized form.

Tokenized Deposits: Deposits are a form of money created by commercial banks based on credit, i.e., Credit Money. Transactions involving tokenized deposits directly lead to changes in the commercial bank’s balance sheet, with tokenized deposits being the tokenized expression on the blockchain.

Legal Stablecoin: Here, legal stablecoins refer to stablecoins issued by legally regulated institutions, such as the Australian dollar stablecoin A$DC issued by ANZ, Australia’s third-largest bank. Since stablecoins are bearer instruments, transactions involving them do not reflect changes in the issuer’s balance sheet but rather transfer between different individuals’ wallets.

Let’s delve further into the application scenarios that on-chain legal currency can bring:

Programmable Digital Currency:

One of the advantages of tokenization is programmability. For tokenized legal currency, programmable money opens a door to a world full of imagination. For instance, in 2023, the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) released a technical whitepaper on Purpose-Bound Money (PBM), a digital currency standard that allows for the programmability of the use of currency without programming the digital currency itself, preserving its fungibility through the use of “wrapper contracts.” For more details, you can refer to the PBM whitepaper. The core idea is to use a “wrapper contract” to encase and manage generic digital currency, placing the payment logic within this “wrapper contract” to manage the digital currency inside it. For different application scenarios, we can choose different “wrapper contracts” to constrain and manage the encased digital currency, thus achieving a programmable effect on the payment process and conditions. However, these wrapped digital currencies remain uniform, neutral, free, and fungible. Once conditions are met, the recipient can extract the digital currency from the wrapper, restoring the digital currency’s inherent “unconditional” nature[21].

In essence, using PBM technology to program money allows it to be used for specific purposes and automatically revert to a fungible currency form once conditions are met. For example, a government might issue dedicated funds to stimulate a particular market, such as the peach market, where the funds can only be used to purchase peaches. Or, parents could set up a fund lock for their child, ensuring that only a certain amount is unlocked each month to regulate spending. However, this technology could be controversial because, while it provides governments with more precise means of currency control, it also implies greater regulatory authority, potentially leading to losses in privacy and freedom.

Real-world Application Scenarios:

Previously, blockchain technology faced numerous obstacles in actual industrial applications, resulting in some non-Token blockchain projects merely becoming expensive and inefficient database systems. Even blockchains with Tokens could not fully realize their potential due to legal regulations and the gap between on-chain and off-chain systems, with the absence of on-chain legal currency being one of the reasons. Let’s illustrate this with an RWA case.

In the crypto world, some RWA projects attempt to tokenize and sell shares of real-world rental income rights on the blockchain. Implementing such operations faces barriers due to the on-chain/off-chain gap. For example, if tenants pay rent in off-chain legal currency, the project team needs to convert the tenant’s rent into on-chain stablecoins and then distribute the rental income to investors holding shares. Setting aside the friction costs of converting off-chain money into on-chain stablecoins, there’s also the issue of transparency regarding whether tenants have genuinely paid the rent, not to mention compliance and regulatory issues, such as how disputes are handled or what happens if the project team absconds.

If established on a system with on-chain legal currency and a legally regulated permissioned chain, tenants could naturally pay directly using on-chain legal currency to the corresponding smart contract, which would automatically distribute according to the financial product’s share allocation to all investors holding shares. Using token standards like ERC-3525, issuers can easily package various non-standard rental income rights assets into a standardized financial product. Its transparency also allows investors to know if tenants have genuinely paid the rent. Furthermore, the issuer could repackage many such financial products into a financial product of financial products.

In summary, the widespread adoption of on-chain legal currency, especially the extensive application of CBDCs, will inject strong momentum into the mass application of real-world asset tokenization. This not only creates real scenarios for the application of tokenization technology in our daily lives and various industries but also brings broader prospects and possibilities, potentially having a significant impact on various aspects of people’s daily lives.

Oracles and Cross-Chain Protocols

Despite the revolutionary potential of blockchain and tokenization technologies, the operational mechanism of blockchain, where each node must perform deterministic operations — that is, for the same input data, all nodes will produce the same output result — introduces challenges. When nodes acquire and process external data, they face non-deterministic operations. This uncertainty can lead to inconsistencies among node data, thereby affecting the consensus process. Thus, blockchain cannot actively acquire data from external sources, a challenge known as the “oracle problem.”

Most potential applications of smart contracts must connect with off-chain data and systems to be realized. For example, in the financial sector, smart contracts executing transactions depend on external market price data; in insurance, smart contracts processing claims must make judgments based on IoT and web data. Smart contracts in trade finance require access to relevant documents and digital signatures to confirm and execute loan transactions. Moreover, many smart contracts need to interact with traditional payment networks for fiat currency transactions during settlement, yet much of the necessary data is generated off-chain and cannot be directly transferred to the blockchain.